Warning that semantics are going to be tricky on this one. As per usual. The word "loving others" can, in spirit, mean so many things that it becomes an almost useless tool of precise communication.

Looking at what love can and is used for as a term I think reveals some interesting points about why "we can solve the world with love" isn't going to get the job done.

Work in progress. Potentially controversial. Hypothesis of decently high likelihood of "agree on ideas, disagree on phrasing because I'm reading the words different than you". And some aspiration of humility that I probably haven't fully figured this out and my own thoughts need adjustment and tweaks, maybe even overhaul.

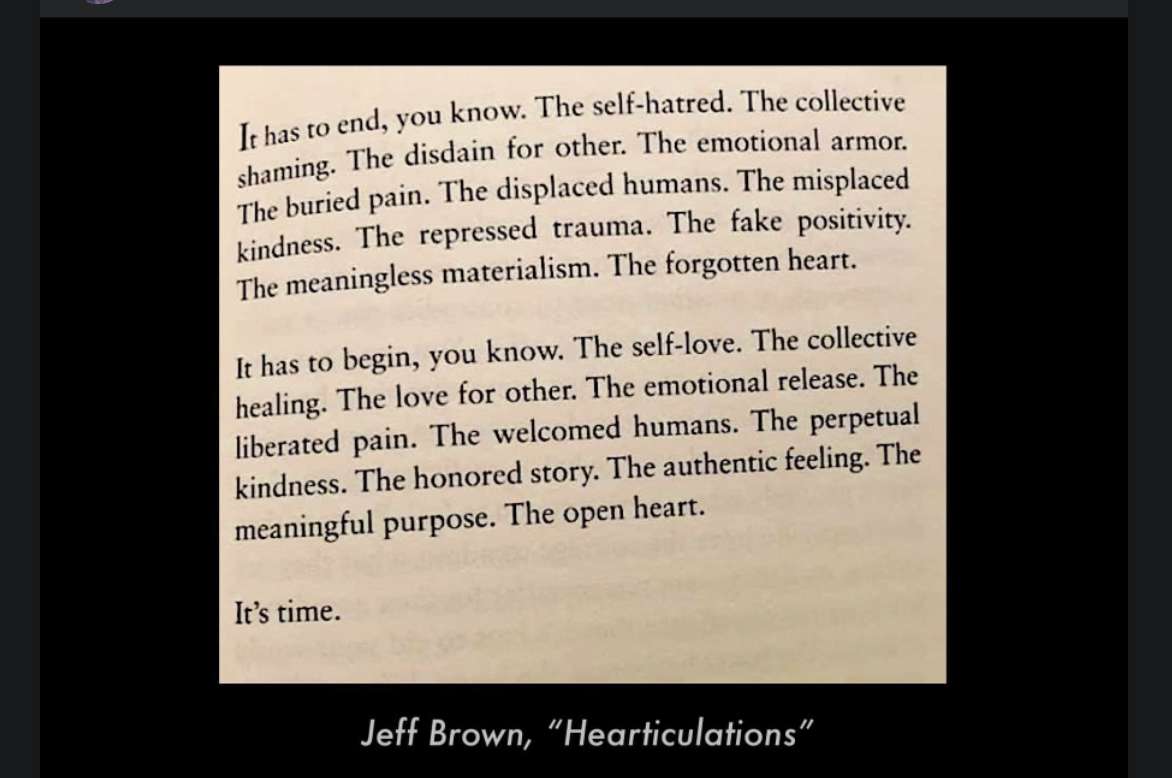

This piece is a response to this social media image sharing a passage by Jeff Brown. It's not, perhaps, the best example of "love is the answer", but it's close enough and this is a topic I've wanted to explore and critique for a while. This passage triggered me enough to get a first crack at writing that critique out. See below for passage and critical thoughts about the topic an why love is not all we need.

I'm starting to feel like we need less "love", because people disagree over what expressing love looks like. And instead need more self-accountability for questioning own opinion. Hearing out the other. And skill in not accepting "agree to disagree" but instead putting the hard work of truly understanding other.

- Gay conversion therapy is often done out of love. Misguided, but actual love.- Calls for compliant obedience are often done out of worry, rooted in love, that harm will come from non-compliance

Maybe that can be labelled "doing love wrong", but I think it's something else. I think it's genuine and real love, expressed through an arrogant insistence that self has the facts right and the object of love has the facts wrong.

Jeff Brown I feel misses this and other points quite often. I support some of his ideas but think he has it wrong other times. I won't insist that I'm right, but I often feel Jeff Brown will insist I agree with him, or else face shunning and ostracization.

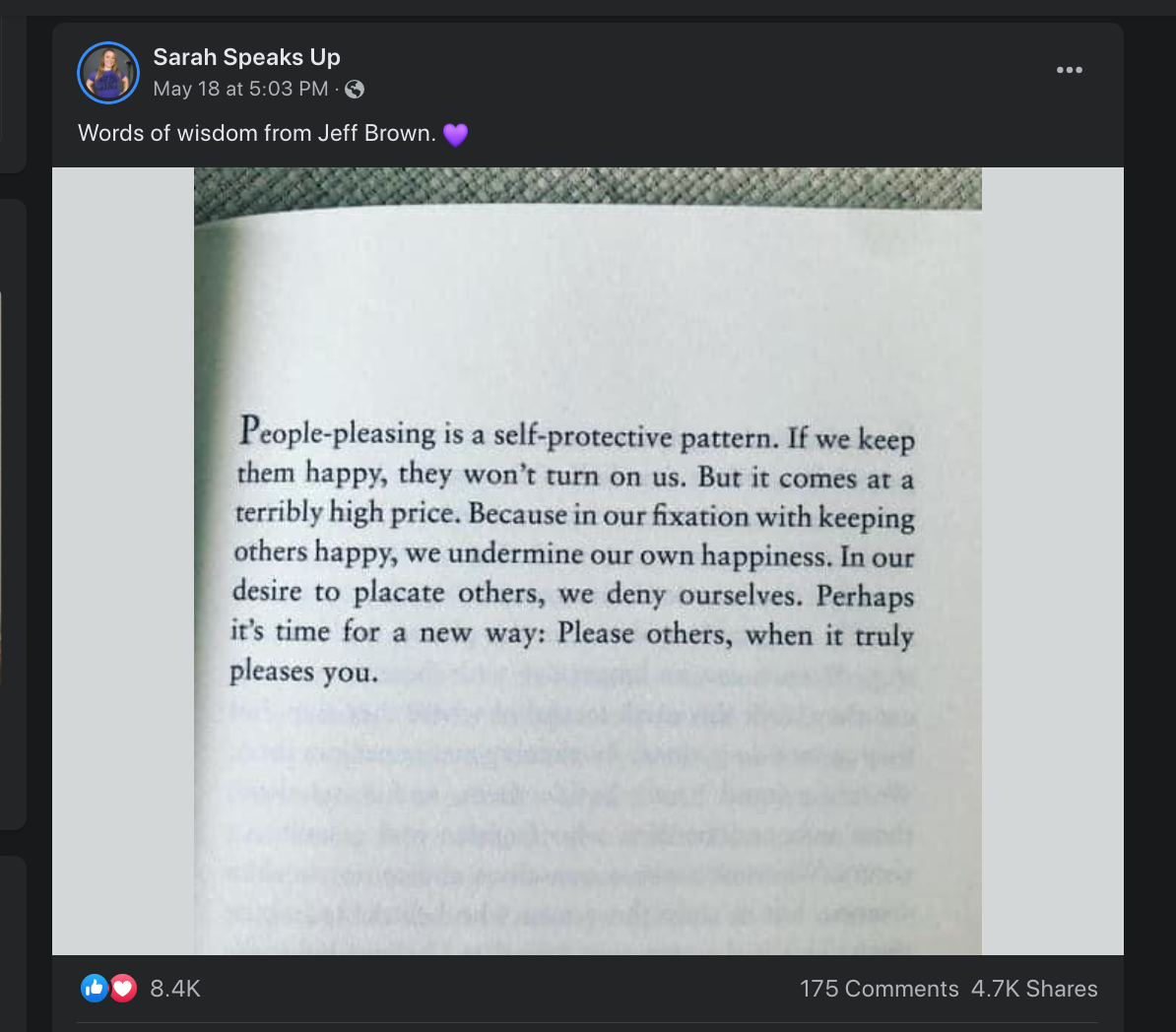

Which is then justified by a false narrative that I am wholly and totally self-empowered to love myself, which denies the harsh reality of dependence on at least some interaction with others.